“A hypothesis is the most important tool for scientific inquiry. Without a hypothesis, there can be no experiment.”

— Jerome Bruner, American Psychologist and Educationist

Your hypothesis is the foundation of your entire research paper. It’s the central pillar that supports all your arguments, methods, and conclusions. Without a strong, clear, and testable hypothesis, your research can feel directionless, and your arguments can fall flat.

But how do you go from a general research question to a powerful hypothesis? It’s not about making a wild guess; it’s about crafting a precise statement that you can prove or disprove.

In this guide, we will break down the entire process into five simple, actionable steps. You’ll learn how to write a hypothesis from scratch and see plenty of examples along the way. Let’s start.

What Is a Hypothesis? A Simple Definition for Beginners

A hypothesis is a statement, an educated, testable prediction about the outcome of your research. It’s more than a topic, and it’s more specific than a question. A question asks something; a research hypothesis proposes a particular answer to that question.

Think of it as the bridge between your general idea and your specific research. A good hypothesis is a clear, definitive statement that often follows a simple “If… then…” structure.

Example: If a student studies for at least five hours a week (the cause), then they will achieve a higher test score (the effect).

This statement is not a fact. Its purpose is to provide a clear direction for your research. Your job is to collect and analyze data to see if you can prove or disprove it.

The Importance of Testability and Variables: The Two Pillars of a Good Hypothesis

A. Pillar 1: Testability. This is the most important rule. Testability means your hypothesis must be something you can actually prove or disprove through observation, experimentation, or data analysis. You cannot “test” a statement of opinion.

- Untestable: “Dogs are better than cats.” (This is a subjective opinion.)

- Testable: “Dog owners report lower stress levels than cat owners.” (This can be measured through surveys and studies).

B. Pillar 2: Variables. Variables refer to a strong hypothesis that needs to be identified to study the factors you are studying.

- The Independent Variable: This is the one thing you change or control. It’s the “cause.”

- The Dependent Variable: This is the thing you measure. It’s the “effect” that depends on the independent variable.

For instance, “studying for at least five hours a week” is the independent variable, and the “higher test score” is the dependent variable.

Getting these two pillars right is the essential first step. Once you have a testable idea with clear variables, you are ready to start crafting your statement.

What Are the 7 Types of Hypothesis?

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis predicts a straightforward relationship between a single cause and a single effect (the independent and dependent variables, respectively). This is the foundational building block of all scientific inquiry. Its purpose is to isolate a clear cause-and-effect link, making it the most focused and easiest type of hypothesis to test.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis examines and determines the relationship between two or more variables at once, two or more effects, or both. This is where research begins to mirror the real world, acknowledging that outcomes are rarely the result of a single factor. It often evolves from a simple hypothesis when a researcher wants to investigate the combined influence of several different elements.

Null Hypothesis (H₀)

The null hypothesis testing states that there is no relationship between the variables. It’s the default position that a researcher tries to disprove. To be tested in an experiment, the null hypothesis is restated as a statistical hypothesis, allowing for analysis of data sets to see if the outcome is statistically significant.

Alternative Hypothesis (H₁ or Hₐ)

The alternative hypothesis (H₁ or Hₐ) is the logical opposite of the null hypothesis and represents the actual prediction you are researching. This is the statement you believe to be true—the claim you are hoping to find evidence for. In the courtroom of science, if the null hypothesis is the “innocent until proven guilty” stance, the alternative hypothesis is the prosecution’s case. You can only accept it once you’ve gathered enough evidence to reject the null.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis does more than just predict a relationship; it specifies the exact direction of that relationship. This is a hypothesis with a point of view, using confident words like “increase,” “decrease,” “positive,” or “negative.” You use this when existing theory or previous studies give you a strong reason to make a more precise claim. It’s the difference between saying “the weather will change” and “the weather will get warmer.”

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis examines and states that a relationship exists between two variables, but does not predict the direction of that relationship. This is a more cautious and exploratory approach. It is often used when there isn’t enough prior scientific research to make a particular prediction. It essentially says, “I believe X will affect Y, but I’m not yet sure if the effect will be positive or negative.” This allows the data to lead freely without preconceived directional bias.

Empirical Hypothesis (or Working Hypothesis)

An empirical, or ‘working,’ hypothesis is currently being tested through observation and experiment. This is where theory meets practice. It often starts as a logical hypothesis, an explanation based on reasoning, and becomes an empirical one as soon as you design a test for it.

While this might seem like the end of the list, there are advanced ways to develop a hypothesis!

Advanced Hypothesis Classifications

Beyond the 7 common types, hypotheses can also be classified by two other important criteria: their intellectual origin (how the idea was formed) and the nature of the relationship they propose. Understanding these distinctions provides a deeper insight into the scientific method itself.

Classification by Origin: Inductive vs. Deductive

Inductive Hypothesis

An inductive hypothesis is born from observation; it is a “bottom-up” approach. A researcher starts by noticing a specific pattern in the data or a recurring phenomenon and then formulates a generalized hypothesis to explain it. This is the detective’s method: moving from individual clues to a broader conclusion. It is often the starting point for developing a brand-new theory.

Deductive Hypothesis

A deductive hypothesis flows from the “top-down,” starting with a general, well-established theory and deriving a specific, testable prediction from it. If induction is about creating theories, deduction is about testing them. You apply a broad principle to a particular case to see if the principle holds. This is the classic scientific method in action, where the goal is to confirm or challenge an existing framework.

Classification by Relationship: Associative vs. Causal

This classification focuses on the strength and nature of the proposed link between variables. It separates original hypotheses that suggest a simple connection from those that claim a direct cause and effect link.

Causal Hypothesis

A causal hypothesis makes a powerful claim about influence: that a change in one variable will directly cause a change in another. This is the definitive statement of cause and effect. It doesn’t just suggest two events are connected; it predicts that one is the direct result of the other. Testing this type of hypothesis is the primary goal of controlled scientific experiments.

Associative Hypothesis

An associative hypothesis proposes that two variables are related, meaning they change in a synchronized way, but it does not claim one causes the other. This is a statement of correlation, not causation. It points out that as one variable changes, so does the other, suggesting a connection that could be due to a third, unmeasured factor. This type of hypothesis is common in observational studies where a direct experiment isn’t possible. Need Help Crafting Your Own Hypothesis?

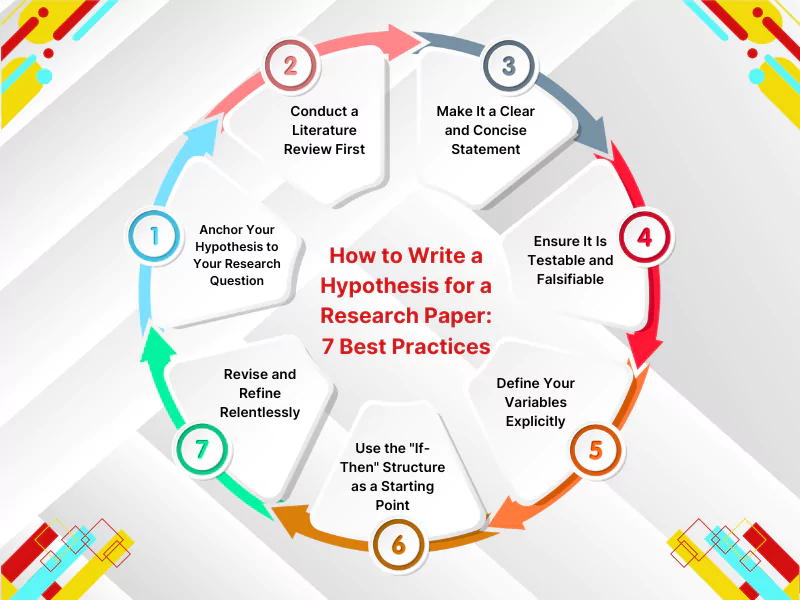

How to Write a Hypothesis for a Research Paper: 7 Best Practices

Your hypothesis requires more than just an idea; it demands precision in the research process, foresight, and a clear understanding of the scientific method. Below are 7 best practices to guide you through this critical process, ensuring your hypothesis is professional, defensible, and built for success.

1. Anchor Your Hypothesis to Your Research Question

Ask a question and answer it! Your research question is the broad inquiry you are exploring, while your hypothesis suggests the specific, testable answer you propose. The two must be perfectly aligned. Therefore, every word of your hypothesis should be dedicated to answering your primary research question. If they don’t match, one of them needs to be revised.

- Practice in Action: If your research question is, “What is the effect of daily meditation on students’ anxiety levels?” your hypothesis may directly propose an answer, such as, “If students practice daily meditation for 15 minutes, then their self-reported anxiety levels will decrease.”

2. Conduct a Literature Review First

A hypothesis in a research paper should never come from a vacuum. It must be an informed statement, grounded in existing knowledge and evidence. Before you write your hypothesis, conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about your research topic. This allows you to identify gaps in the research and position your hypothesis as a logical and necessary next step.

3. Make It a Clear and Concise Statement

If you think a hypothesis is an assumption, it is not. Instead, your hypothesis is a declarative statement, not a question. It must assert a relationship or a predicted outcome with confidence. Aim for absolute clarity and conciseness. In most cases, a single, unambiguous sentence is best. Avoid complex jargon or convoluted phrasing that could obscure your meaning.

- Weak: “It seems possible that in a scholastic environment, the utilization of certain pedagogical techniques might affect student engagement.”

- Strong: “Incorporating project-based learning into the curriculum increases student engagement.”

4. Ensure It Is Testable and Falsifiable

This is the golden rule. You must be able to test your hypothesis through observation or experimentation, and it must be possible to prove it wrong. A statement that cannot be disproven is not a hypothesis; it’s an untestable belief. This means avoiding subjective or value-based words, such as “better,” “good,” or “beautiful.”

5. Define Your Variables Explicitly

A formal hypothesis must identify the independent variable (the cause) and the dependent variable (the effect). Be specific about the populations, measurements, and conditions you are studying. The more precise your variables are, the clearer your research design will be.

- Vague: “More screen time is bad for sleep.”

- Specific: “Adolescents (ages 13-17) who engage in more than four hours of screen time per night report lower sleep quality and shorter sleep duration than those who engage in less than two hours.”

6. Use the “If-Then” Structure as a Starting Point

While not always mandatory in the final draft, formulating your hypothesis using the “If-Then” structure is an excellent way to ensure you have included both the cause and the effect. It forces you to connect your independent variable (the “if” part) directly to your dependent variable (the “then” part), clarifying the logical relationship between them.

7. Revise and Refine Relentlessly

Your first draft of a hypothesis is rarely your last. Put experiments to tests! Share it with advisors, peers, or mentors. Ask them: Is it clear? Is it testable? Is it specific enough? Be prepared to revise your hypothesis based on feedback and as your understanding of the research evolves, if it states the opposite. A refined hypothesis is a sign of a diligent and thoughtful researcher.

If the relationship between variables is not established correctly, you can avail of the Research Paper Writing Service.

What Are the Common Mistakes to Avoid in Hypothesis Writing?

#1: The Untestable Opinion

This is the most common error. A hypothesis must be a claim that can be proven or disproven with evidence. If it’s based on a subjective value judgment or personal opinion, it’s not a hypothesis. Watch out for words like “better,” “best,” “beautiful,” or “wrong.”

- Mistake: “Van Gogh was a better painter than Monet.”

- Why it’s a mistake: The word “better” is subjective and cannot be scientifically measured. There is no experiment you can run to prove this statement definitively.

- Correction: “Art buyers are willing to pay more for paintings by Van Gogh than for paintings by Monet.” (This is testable because you can collect and compare auction price data.)

#2: The Hypothesis in Disguise (The Question)

A hypothesis must be a declarative statement that makes a prediction. It cannot be a question. A research question is your starting point, but the hypothesis is the proposed answer to that question.

- Mistake: “Does poverty affect high school dropout rates?”

- Why it’s a mistake: This is a research question, not a predictive statement. It doesn’t propose an answer or a relationship.

- Correction: “Students from families living below the poverty line have a higher high school dropout rate than students from families above it.”

#3: The Vague or Ambiguous Statement

A strong hypothesis must have clearly defined and measurable variables. If the terms are vague, it’s impossible to design an experiment to test them.

- Mistake: “Too much screen time is bad for kids.”

- Why it’s a mistake: “Too much,” “bad,” and “kids” are all too vague. How much is too much? What is the specific adverse effect? What age are the kids?

- Correction: “Children aged 8-12 who engage in more than three hours of screen time per day exhibit higher levels of hyperactivity than those with less than one hour.”

#4: The Hypothesis That’s Just a Topic

Simply announcing the topic of your research is not a hypothesis. You must make a specific, testable claim about that topic.

- Mistake: “My hypothesis is about the effects of motivation on employee productivity.”

- Why it’s a mistake: This describes a general area of study but does not predict the relationship between the variables.

- Correction: “Employees who are offered performance-based bonuses will have a higher productivity rate than employees who are paid a flat salary.”

#5: The Ungrounded or ‘Fantasy’ Hypothesis

While a hypothesis is a prediction, it must be plausible and grounded in some existing theory or observation. It cannot be a complete shot in the dark that ignores all known science.

- Mistake: “Consuming tap water gives humans the ability to communicate with dolphins.”

- Why it’s a mistake: This claim contradicts everything known about biology, physics, and communication. A hypothesis should be a logical possibility, even if it ultimately proves to be false.

- Correction: Focus on plausible links. A better approach is to begin with a literature review to determine what is already known, and then propose a logical next step for research.

10+ Hypothesis Examples Explained (For Science, Business & More)!

Science Hypothesis Examples

| Research Question | Hypothesis | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Does fertilizer make a plant grow bigger? | If fertilizer is added to the soil, then the plants will grow taller than those without it. | Simple |

| Does sugar consumption cause obesity? | Daily consumption of sugary drinks leads to an increased risk of obesity. | Simple |

| Do dogs eat more if they are larger? | Larger dogs will eat more food than smaller dogs of the same breed. | Comparative |

| Does sun exposure affect mood? | Daily exposure to sunlight increases reported happiness levels. | Directional |

| Are all daisies the same? | All daisies have the same number of petals. | Null |

Business Hypothesis Examples

| Research Question | Hypothesis | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Will offering a discount increase sales? | If we offer a discount on our product, then we will attract more customers and increase sales. | Causal |

| Does price affect sales volume? | Increasing the price of a product will lead to a decrease in sales volume. | Causal |

| Do flexible work hours affect job satisfaction? | Employees with flexible working hours report greater job satisfaction than those with fixed hours. | Directional |

| Will a new marketing campaign drive more conversions? | If we launch a new marketing campaign, then our conversion rates will increase. | Predictive |

Social Science & Education Hypothesis Examples

| Research Question | Hypothesis | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Does education level impact crime rates? | The higher the education level, the lower the rates of crime in a population. | Directional |

| Does study time impact exam performance? | Students who study for three or more hours a day will score higher than those who study less. | Directional |

| Does social media use affect attention span? | There is a negative correlation between social media use and attention span in under-16s. | Non-directional |

| Does breakfast affect academic performance? | Students who eat breakfast perform better in exams than those who don’t eat breakfast. | Simple |

Final Checklist for a Strong Hypothesis

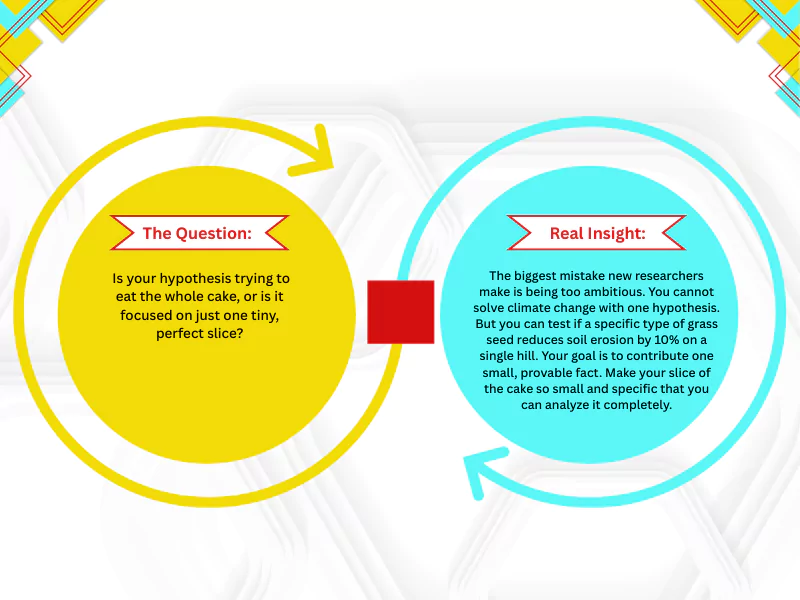

✅ 1. The “So What?” Test

✅ 2. The “Measurement Reality” Check

✅ 3. The “One Slice of Cake” Check

✅ 4. The “Brave Enough to Be Wrong” Check

✅ 5. The “30-Second Hallway” Test

Key Takeaways

- A hypothesis is a clear, testable prediction about the relationship between variables.

- Strong hypotheses are specific, based on research, and include measurable variables.

- The “if…then…” structure helps clarify cause and effect, but should be adjusted for precision as needed.

- Avoid common errors: make sure your hypothesis is not vague, subjective, or a restatement of your topic.

- Effective hypotheses answer a research question and can be proven right or wrong through data.

- Prioritize relevance, clarity, and ethical testability in your formulation.

- Seek assignment help when needed!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Type 3 Hypothesis?

The term ‘Type III hypothesis’ is sometimes encountered in advanced statistical analysis, specifically in ANOVA with unbalanced designs. It refers to a method of testing the significance of a factor after accounting for all other aspects. However, for most introductory and intermediate research, this classification is not used. You should focus on understanding common types, such as null, alternative, simple, and complex hypotheses, as they form the foundation of most scientific inquiry. If you see this term in a specialized context, refer to a dedicated statistical textbook on General Linear Models.

What Is a Good Simple Hypothesis?

A good, simple hypothesis states that the relationship between a single independent variable and a single dependent variable is clear and testable.

Example: “If a plant receives more sunlight, then it will grow taller.”

What Are the Three Stages of Hypothesis?

- Formulation of the hypothesis

- Testing or experimentation to evaluate the hypothesis

- Drawing conclusions based on the results of the testing or experimentation

What Are the Three Parts of the Hypothesis?

- The variables being studied (independent and dependent)

- The relationship or expected effect between them

- The population or subject group involved

What Is an Example of a Famous Hypothesis?

What Is an Example of a Hypothesis Statement?

Related Blogs

- How to Access Chegg for Free in 2026? 7 Clever Methods - December 5, 2025

- Practical Learning Vs Theoretical Learning: A Comprehensive Guide - September 3, 2025

- How to Use English Techniques? The Ultimate Guide - July 29, 2025